Analyzing Roberto Ferri's Pietà Occulta

Italian artist Roberto Ferri is a modern-day symbolist painter, deeply inspired by Baroque artists like Caravaggio. His peculiar reintroduction of nature into his otherwise Apollonian work frequently leaves the viewer begging for an explanation. A logic is present, but dips beneath consciousness, evading simple explanations and rational models of expression. In an attempt to better understand the symbols he employs in his work, and introduce him to a general audience, I will analyze his parodic painting, Pietà Occulta (2018).

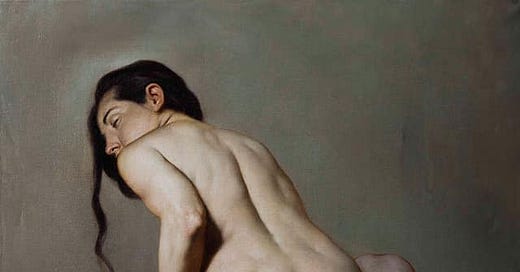

A starburst against the shaded background is the light skin of a contained woman. Her rich and living skin is a testament to her abundant vitality. She is a representation of a woman, and nature herself, her too-muchness narrowly contained by the splintering grip of civilization. We are gifted a homage and inversion. Michelangelo’s Pietà features the Madonna carry her dead son Jesus, lamenting his passing and holding him forward as an offering to the world. It is a symbol of the Archetypal Good Mother who, like all great mothers, sacrifices her son to the world of men, society imbued with triumphant values. Thus, he symbolically transcends his nature and home, bearing his cross in the whirling cosmos.

The title Pietà Occulta suggests an inversion of the healthy mother-son dyad. Therefore, we see the woman, with her rich dark hair and nude body (her relationship with her son is “exposed”) as the Devouring Mother, an Archetype glanced by Sigmund Freud in his discussion of the Oedipal Complex. Thus, the woman is the man’s mother, and his devourer, feeding on his life force. A vampire, seductress, and enticing witch, she tempts her son back into infancy where they will be unified forever. There, she provides, and dictates his course of life – permanently securing him as a fixture in her toxic womb.

The faceless son, with no identity of his own, clings to her. His granite fingers crease the skin of her rear and thigh. He nearly tears into her flesh, crying all the while. He is lower than her, and his head is placed at the height of a child. She does not protest. Her arms do not create distance between them, extended to signify her quest for autonomy, but rest on his shoulder for support. He is her crutch and pillar. Her face is not twisted in agony or frustration but relaxed into comfortable resignation. To his infantile cries she responds, “yes, of course.” There is warped warmth in her quiet gaze, perverse contentment. His sexual grip on her body betrays longing and cowardliness. Often, sex is a symbol of unification and Oedipal incest plays the same role here.

The boy is turned to stone. He is immobile, lacking vital living energy. His impotency, a stagnation in the sea of infancy, renders him brittle – an ocean against stone. Small rocks break from his body. Cracks have emerged on his legs and arms, suggesting the fate of their relationship: He will die, and her nightmare of loneliness will be realized. He is grey and lifeless, and his dark shade blends him with into the background, where he will remain.

In the background, obscured by their bodies, are the ghastly tendrils of nature; “occult” comes from occulere, “to conceal.” The hidden roots from terra materna sink into his back, claiming his corpse for the soil; another seedling to be harvested by Death’s scythe. Their slinking, slithering course recalls the uroboros – the great python at the base of the world tree. It is the Archetype of initial chaos from which all things are born, and eternally return to. The symbolism of the uroboros is tens, perhaps hundreds of thousands of years old. It is the initial deity who whispers in the garden of Eden.

In the bursting lamentation of Pietà Occulta, a lesson manifests: The mother who fails to encourage the development of her son’s identity, and the son who fails to assert it, will become brittle and decay into primordial chaos.